Planet

The climate crisis is unequivocally caused by human activities and the fashion industry is one of the most detrimental contributors with textile production alone emitting “1.2 billion tonnes of co2 annually”.[1] Out of the four pillars, “Planet” is arguably the pillar in which gen-z have the most heightened sensitivity to, as we realise that, ultimately, we cannot sustain a system that is not working.

Sustainability in relation to fashion is ensuring that we as stakeholders, (both producers and consumers), are meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

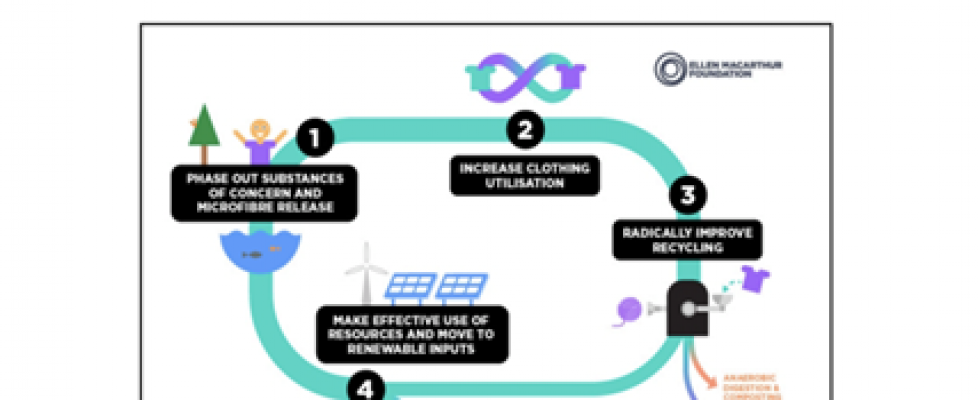

Moving forward, key stakeholders in the fashion industry need to consider alternative business models, and recognise that design has become the most powerful tool with which man shapes his tools and environment [2], as we shift from a linear model of “take, make, waste” and replace this with a circular model. This is a system in which clothes remain in the loop until their maximum value ceases to exist and when this occurs, they are returned to the biosphere safely. A common misconception is that recycling should be the prioritised goal, however recycling should be a last resort as it involves spending resources and energy to deconstruct the product and then use more to generate a new product. To maintain the garments health and keep it in the system for as long as possible, repairs are made in addition to reusing either by sharing or renting. The Ellen Macarthur foundation have outlined a “vision for circularity in fashion”, which involves advice for stakeholders regarding this concept. (see below)[3]

Furthermore, Patrick McDowell, designer and founder of his self-titled brand, highlights the importance of curating smaller collections and how it is possible to show the same body of work repeatedly by restyling looks which is less wasteful and thus more environmentally conscious. He is an example of a smaller brand “shifting to a demand driven model”,[4] meaning there is less overproduction.

In order to generate the change that needs to occur, radical collaboration is a solution that must be considered, as it is too often the case that “voluntary action is only taken by leaders”[5], and without strict legislations change is momentary. Instead, stakeholders must cooperate through sharing knowledge and designing with intent. An example of this is through the Sustainable Development Goals, which were curated over a period of 2 years by the United Nations. They are important as they apply to every nation and every sector, requiring universality. Each of the 17 goals are split into either environmental, social or economic goals and an example is clean water and sanitation. This goal is intrinsically linked to fashion, as textile and garment production is water intensive, using approximately 79 billion cubic metres of water every year. [6]While many economically advanced countries are practising less harmful techniques, some countries and companies continue to knowingly release byproducts and chemicals into local water systems, which not only shows a lack of care and responsibility but is detrimental to the health of local inhabitants. Cleaning waters requires investment and a shift in mindset and an example of this is that several manufacturing hubs have begun working with technology which is capable of saving 50 million litres of water. This is one example which highlights the importance of radical collaboration when generating change.

[1] Leal Filho, W. et al. (2022) An overview of the contribution of the textiles sector to climate change, Frontiers. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.973102/full#:~:text=Due%20to%20its%20complex%20supply,emissions%20(UNFCCC%2C%202018). (Accessed: 08 October 2023).

[2] Wahl, D.C. (2017) Visionaries of Regenerative Design V: Victor Papanek (1927–1998), Medium. Available at: https://designforsustainability.medium.com/visionaries-of-regenerative-design-v-victor-papanek-1927-1998-57019605997#:~:text=Papanek%20repeatedly%20emphasized%20that%20%E2%80%9Cthe,past%20as%20well%20as%20the (Accessed: 08 October 2023).

[3] Macarthur , E. (2022) Circular-ish: embracing the messy reality of circular economy innovation, Embracing the messy reality of circular economy innovation. Available at: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/articles/circular-ish-embracing-the-messy-reality-of-circular-economy-innovation (Accessed: 08 October 2023).

[4] Moran, G. (2022) Collaborating for change: Sustainability report 2022, Drapers. Available at: https://www.drapersonline.com/guides/collaborating-for-change-sustainability-report-2022 (Accessed: 08 October 2023).

[5] Moran, G. (2022) Collaborating for change: Sustainability report 2022, Drapers. Available at: https://www.drapersonline.com/guides/collaborating-for-change-sustainability-report-2022 (Accessed: 08 October 2023).

[6] Reducing the fashion industry’s water footprint (2022) Recover. Available at: https://recoverfiber.com/newsroom/world-water-day#:~:text=The%20impact%20of%20fashion%20on%20water&text=It’s%20estimated%20that%20the%20industry,but%20also%20dyeing%20and%20treatments. (Accessed: 08 October 2023).